Working on "Mill Hill"

Gray Building: Erwin Mills headquarters on West Main Street (formerly called Mulberry Street).

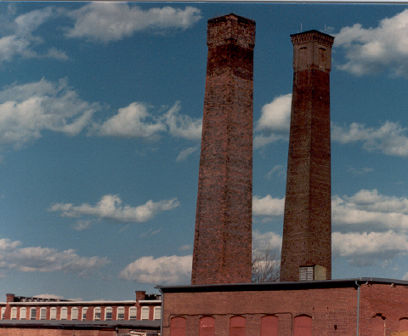

Old brick smokestacks: Now long gone, this is the site of a proposed Erwin Square apartment complex that will reflect the mill's heritage.

William Pickett,

Loom Fixer, in the Weave Room of Old No. 1 Mill (1973). Today, Old No.

1 is the red brick building with offices and apartments on Ninth Street

(below).

Carl Moore worked all his life in Erwin Mills. Moore is standing in the Weave Room/North End -- near present-day George's Garage (below). Loom Fixers had better pay than Weavers. Moore is standing in front of a Draper Loom (which was replaced by a modern Sulzer Weaving Machine). In a nod to progress, folks stopped calling these "Looms" and started calling them "Weaving Machines."

Four generations on Mill Hill: Bobby Jackson (left) and Bobby Jackson, Jr. Says Bobby, Jr. "My grand dad, Willie Jackson, worked at the mills. My great-grand dad, Clifton Jackson, worked at the mills. If the mills hadn't shut down, my sons would still be working at the mills." Family home was at 714 Iredell Avenue (near Perry Street).

714 Iredell today.

Bobby Jackson, Jr. recalls that his union (Local 257) set up shop in a small wood building at Rosehill and Hillsborough (today, the back of West Durham Tire). During a short-lived strike, the union handed out a small amount of food items to the striking workers once a week -- at the end of Rosehill Avenue.

"This was around 1950 because my Mother remembers that she was expecting my oldest sister during this time," Jackson said. "My Grandfather on my Mother's side ran a Cafe there years before when my Mother was just a teenage girl. His name was Buck Carden."

Worker Unrest

Mary Harris "Mother" Jones (1836-1930) was a union organizer who was denounced in the U.S. Senate as the grandmother of all agitators. In 1903, Mother Jones organized a march of striking children from the textile mills of Kensington, Pennsylvania, to petition President Theodore Roosevelt. He refused to see them, but the march helped to raise national awareness of the plight of child workers.

Working conditions during the Great Depression brought relations between mill workers and management to a boiling point. In September 1934, tens of thousands of textile workers throughout the South walked off the job protesting conditions at the mills and in company-controlled mill villages. According to the News & Observer, hundreds of striking Erwin Mills workers rallied at the Carolina Theatre, marched down Main Street and enjoyed widespread community support.

The General Textile Strike of 1934 ended three weeks later with some 20 workers dead from strike-related violence, others sitting in internment camps and little progress for the "lintheads," the pejorative term for cotton mill workers. Years later, the memory of the strike (considered by historians the largest labor revolt in Southern history) has faded along with the mill villages it helped eliminate. In a part of the country where "union" often has the status of a four-letter word, the strike showed that Southern workers can organize for change even during the Great Depression and amid the constraints of having the mill as employer, landlord and store owner.

The textile worker's union set up shop on the second floor of Brewer's Pharmacy (now the Campus Florist on Ninth Street). Union-Local 257 later moved to a small wood building at Rosehill and Hillsborough (today, the back of West Durham Tire).

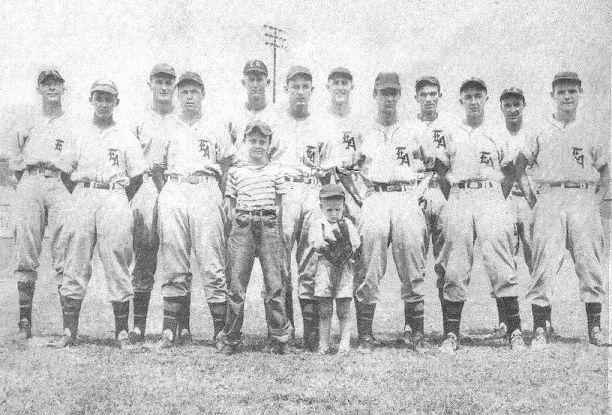

Work & Play: Erwin Auditorium baseball team

Front Row Left to Right: Troy Williamson, Amos Odom, Bat Boy Kemp Bennett, Claiborn James, unidentified young boy with glove, Buck Durham, Ed Williamson and Bill Cheek

Back Row Left to Right: Charles Glen "Cocky" Bennett, G.C. Earp, Malcome Earp, Dick Pierce, Harold Wilkins and Russell West.

Photo courtesy of Norman Pendergrass