The following text was transcribed mostly by machine from a document provided by John Schelp .

The E. K. Powe House, Its Setting and Revival

Presented by E. K. Powe III at a meeting of the Historic Preservation Society of Durham on Sunday, October 4, 1987.

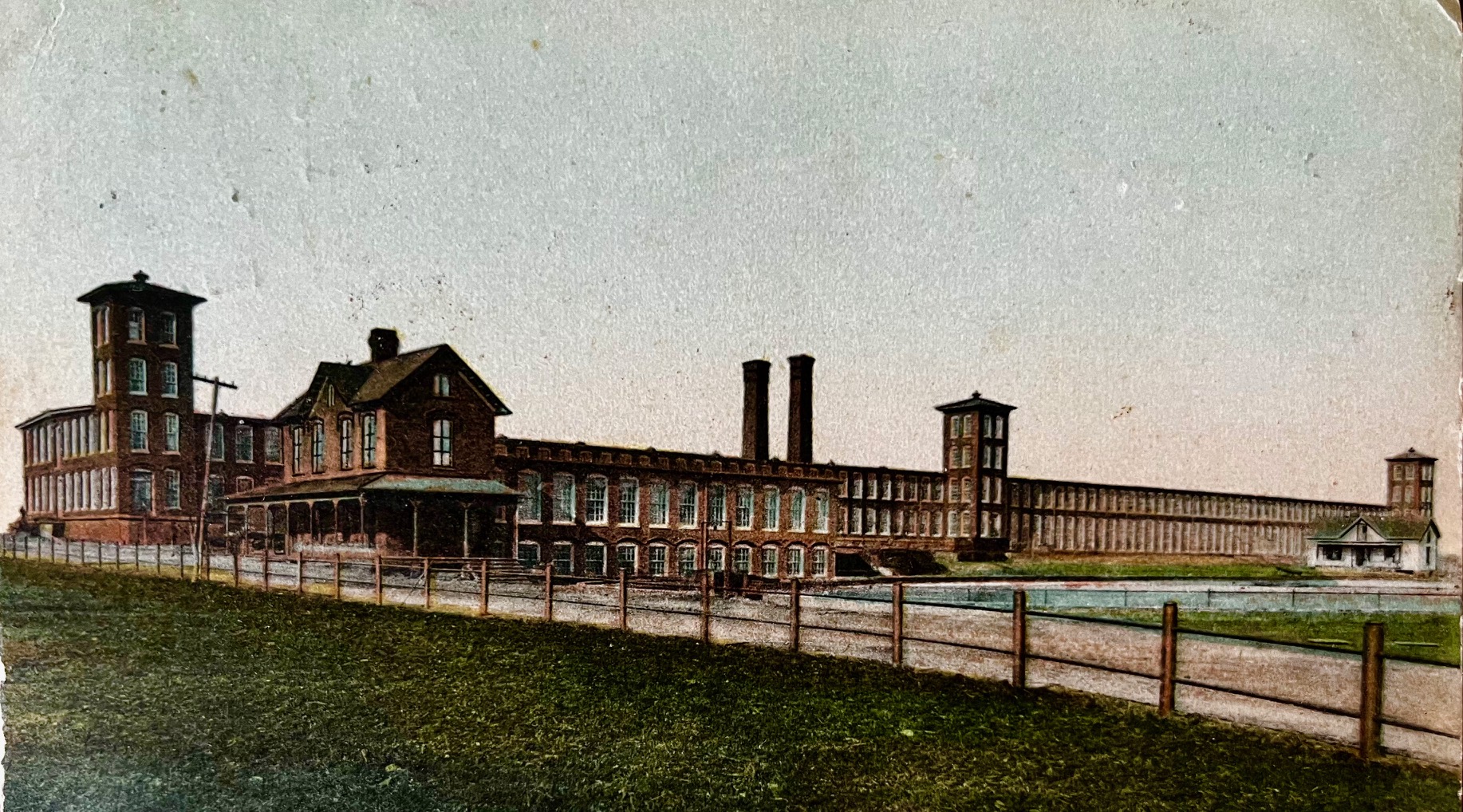

In 1900, when my grandfather, Edward Knox Powe, built his white-columned Neo-classical revival house in West Durham, its location was considered to be "out in the country." There were not many other houses in the area (the Blacknall's and Lyda Duke Angier's being two of the large ones), but the rail road that created Durham ran right in front of the E. K. Powe house, and there was a brand new brick textile mill at the bottom of the hill. Evidently, my grandparents did not feel isolated in this rural setting because my grandmother's two brothers built lovely homes on either side of the Powe house, one in the late 1800s and the other in 1904. I suppose one might say that the completion of these three homes marked the beginning of the Erwin-Powe compound which figured so prominently in the future of the textile industry in the South.

It all came about when Ben Duke and George Watts brought my Great Uncle William Allen Erwin to Durham to start a mill for the manufacture of muslin bags for Duke's smoking tobacco. Although all three men put up money to capitalize the mill, Duke and Watts decided to name the mill for William Erwin. They figured that if it were unsuccessful, William Erwin would have to bear the stigma; if it turned out to be a success, they seemed willing for him to have the credit.

Prophetically, the venture was a tremendous gamble, accentuated by the depression which began just as the mill was getting started. As a result of that difficult economic time, some textile mills closed, but the Erwin Mills was able to keep its doors open. Soon the mill began to make denim, ultimately becoming one of the largest denim manufacturing companies in the nation.

One of the first things Uncle William Erwin did when he came to Durham was to invite my grandfather to be the superintendent of the new Erwin plant. Grandfather Powe had just married William Erwin's sister, Claudia Josephine Erwin, who was from his hometown, Morganton. At first they lived in a frame house at the corner of Powe and Pettigrew Streets; but E. K. Powe must have felt the need of a larger house in which to raise a family; and perhaos he was remembering that his wife had grown up at beautiful Bellevue, a historic post-Revolutionary War house in Burke county. Mr. Ben Duke offered to help out financially; but Grandfather Powe is purported to have responded, "Thank you, Sir, but we just want a simple house."

My grandmother's other brother, Jesse Harper Erwin, also came to Durham to be a textile mill executive. He joined the Durham Cotton Manufacturing Company and later the Pearl Cotton Mllls and was on the Board of Directors of the Erwin Mills. He built his home on the west side of grandparents and named it "Sunnyside." William Erwin's house sat across a dirt lane on the east side of the Powe house, and it was named "Hillcrest." It's interesting that my grandparents' house didn't have a name. Everyone just referred to it as "The E. K. Powe House."

Mill Village

Before long, a villiage began to grow up around the Erwin Mill which stood only a block from the Erwin-Powe compound. William Erwin and E. K. Powe, encouraged by Mr. Duke and Mr. Watts, began building houses for the mill workers' families. At one time, there were 440 neat little houses in West Durham, all with front porches and all painted white or pale yellow. I remember when they rented for $.25 a week per room. All the mill employees were white in those days; the blacks were mostly employed in the tobacco factories.

The Mill management also built a company store, a post office, a park (before Durham had a city park) and a fine brick auditorium. The auditorium was designed to include a library, an ice cream bar, a stage, a gym and even a swimming pool in the basement. In the park there were tennis and basketball courts, a baseball diamond, a playground, bandstand, and a small animal zoo that contained monkeys, bear and an alligator. Once all the monkeys escaped from their cages, but were eventually captured near the mill housed behind my grandparents' house. Afterwards. that area was sometimes called "Monkey Bottom" by some employees.

Across the street and across the railroad track from the Erwin-Powe houses, the family built a pretty stone English parish-style Episcopal Church for the mill workers. It was named St. Joseph's and given in honor of my grandmother's parents, Joseph and Elvira Jane Holt Erwin. Except for prayer meetings and on Sundays during the World War II gas rationing, the Powe-Erwin families rarely attended this church as they were all loyal parishioners of the St. Philip's Episcopal Church on East Main Street. But William Erwin kept a sack of potatoes by the lecturn so if he heard of anyone beating his wife, he could throw a potato at them. West Durham, as the area around the mill was called, became a true mill village. In the early days, it was strictly supervised by William Erwin. Legends abound as to his involvement with the mill families. Example: if he heard that one of the daughters of an employee was acting too amorously with young West Durham men, he would admonish her Parents to correct the situation, or be fired!

This atmosphere was a far cry from the reputation that the western end of the county had inherited. It seems that prior to the Civil War, when Durham Countv was still nart of Orange, there were taverns, grog shops, and rather rough living conditions in the area, originally named Pin Hook. One old tavern keeper, out off the Hillsboro Road near the Bennett Place, was rumored to have murdered his guests, stuffed their bodies in a well, and taken their horses to Raleigh to sell. Local historians have recorded that because of Pin Hook's harsh reputation Meredith College would not move to Durham. Trinity College almost moved elsewhere.

Such tales did not deter the Erwin and Powes. They wanted their community to be a good place to work and raise a family. Their strictly supervised mill village quickly put an end to those legendary uncivilized ways of the past. By the time Durham had reached a population of 5,000, William Erwin boasted (Quote) Moral conditions of my town, West Durham. are better than any in the city (End quote)

E. K. Powe Benevolences

Although textile mills and tobacco factories in the South were noted for their low wages and long work shifts, the Erwin Mills, with the support of Ben Duke and George Watts, pioneered in eliminating child labor and reducing the number of work hours. As superintendent, E. K. Powe was concerned about the welfare of the workers and their families. He could not just look at them as a labor force; he considered them as individuals. Without fanfare, he became involved in their lives in a way that would never occur in today's nonpaternalistic system. As he walked through the mill village, he would stop to talk to the workers in their yards and on their front porches. He invited them to band concerts in the park. He took them rose bushes to pl ant in their yards, many of which are still blooming in West Durham today.

All my life, I have heard from Erwin Mill families, some who were three-generation employees, that Grandfather Powe was beloved in West Durham because he demonstrated that he really cared about the mill people. Time and again, I have been told instances of his benevolence and how he offered assistance with their illnesses, handled burial arrangements at death, etc. It is true that the Erwin Cotton Mills gave hams and clothing to the employees at Christmas, but it was Edward Knox Powe who knew the sizes for the clothes, how many children in each family and what their needs were.

He was particularly interested in the mill children's educat1on and gave great encouragement towards keeping West Durham children in school. I quote Claudia Roberts Brown, an editor of THE DURHAM ARCHITECTURAL AND HISTORIC INVENTORY, in describing his assistance: (Quote) At a time when it was virtually impossible for a mill worker to pay for the children's higher education, Powe quietly paid the tuiticn and related expenses for many of the brightest West Durham students. (End quote)

Grandfather Powe served on the Citv School Board and CityCounty Board of Health. Becuase of his commitment to public education and in recognition of his philanthropy in West Durham, the new graded school on Ninth Street was posthumously named for him.

The mill was so close to my grandparents' house that when the large brass mill bell (which sits today in front of the City's fire station) rang for lunch, my grandmother could hear it and she would know that it would be only a few minutes before her husband would arrive for the big mid-day meal she always had prepared.

House Setting

The E. K. Powe house, large and comfortable, was situated on 4.12 acres of land which extended all the way to Hull Street, just below where the Alastair Court Apartments now stand. The house was reached by a drive that commenced between four large stone pillars at Pettigrew Street and evenly divided a well manicured front lawn. White oaks bordered the drive and two large magnolia trees framed the entrance to the tall white, slate-roofed house. An unknown architect gave the front of the house a graceful two-story portico, but if you look carefully, you'll notice that the front door is not centered between the columns. This is probably due to the stairwell in the foyer. Such a discrepancy in alignment, however, never seemed to bother my grandparents.

A wide and inviting porch, including a small screened porch at one end, wrapped around three sides of the house. The porch, with its tall columns supporting delicate Ionic capitals of terracotta and wide cornice decorated with garlands in relief, made a suitable setting for that popular pastime known in the South as "visiting."

My aunt, Claudia Erwin Powe Watkins, who grew up in the Powe house with her only brother, my father E. K. Powe, Jr., remembers white wicker furniture and rush-bottomed rockers on the front porch and a swing on the screened end. It was a meeting place for neighbors and family, and because there was no air-conditioning, everyone sat on the porch after supper until it was cool enough to retire. Another front porch pastime was watching the train go by. There used to be a little wooden station just before the Ninth Street overpass where passengers could board the train. You would hear the shriek of the whistle when the train was about to arrive.

At the east end of the Powe house, there was a porte cochere which was built to receive horse-drawn carriages -- the only mode of transportation the family had at that time. The horses were stabled in a barn at the rear of the lot and the carriage was kept there too. Although Claudia says she was too young to remember much about the carriage, she does recall the one next door at Uncle Harper's because it was fancier and had fringe around the top.

Claudia thinks her father bought one of the first automobiles in Durham, a Hudson with wide running boards and two spare tires at the front. She remembers her brother hopping out to light the headlights at twilight. (According to her, Dr. John Manning may have had the first car in Durham.)

Near the porte cochere, mock orange trees were fragrant in spring, and pale-blossomed apple trees lined the sides of the property separating the Powe and Erwin homes.

The lot was much wider than it is now because Swift Avenue was only a narrow dirt lane in those days. Subsequently, on two different occasions, the city bought part of the east yard in order to widen the street. (The street had been named for a Mr. J. W. Swift who sold the land to Ben Duke, who sold it to the Powes.)

A two-acre garden was planted at the rear of the house. Grandfather Powe took great interest in it although an excellent gardener, Robert Bowling, did most of the work.

Robert Bowling planted high fig bushes, pink and red raspberries, dewberries, and two kinds of grapes -- scuppernongs on an arbor and bunch grapes in rows (each bunch having to be tied in a bag to keep the birds away). There were quince, pear, and cherry trees to provide fruit for Grandmother Powe's jellies and preserves, and there were several pecan trees which bore enough nuts for her baking. In addition to the vegetable garden, there was a cutting garden filled with bright-colored annuals and perennials.

There was a cow in the barn to be milked, Plymouth Rocks and Red Leghorns in a chicken coop, and prize turkeys fattening for Thanksgiving and Christmas fare. Because Grandfather Powe enjoyed bird hunting, he kept bird dogs in a pen in the backyard.

A good deal of the food at the E. K. Powe table came from the garden. Like the elegant setting across the lane at Uncle William's, he had a fancy race track in his backyard and kept two kinds of thoroughbred horses: carriage and race horses. One, named "Baxter," came in third at the Kentucky Derby.

As to the interior of the Powe house, the foyer was quite spacious and had the added warmth of a fireplace which burned coal. (As a matter of fact, there were seven fireplaces in the house, a corner one in each of the main rooms, which leads us to believe that there was no central heat when the house was first built.) A super Hetradine radio with two headsets and a Gramophone for playing records were kept in the foyer. Also, my great-great-grandmother's spinning wheel, now in the possession of Claudia's daughter-in-law Mary Helen Watkins, sat in the curve of the stairs.

Two of the downstairs rooms were designed with bays and French doors opening into the hall. The front room to the right was the formal parlor where the upright piano stood, and the sunny room to the left was where the family usually sat, except in summer when they were out on the wide front porch. E.K.Powe Family Life

Originally, the kitchen was separate from the house, being connected to the butler's pantry by a porchway. An icebox stood in the porchway and was regularly filled with big blocks of ice by the iceman who arrived in a horse-drawn wagon. Claudia remembers that her mother had three pounds of butter mailed once a week from the town of Hurdle Mills, made by Mrs. Hurdle herself, and molded with an "H."

Grandmother Powe owned one of the first refrigerators that was sold in Durham. However, she would only use a wood stove for cooking and baking, even long after she bought an electric one.

Upstairs, there were originally only three bedrooms. Later an ell was added to the rear of the house which included an additional bedroom, another bath, a back stairway, and a large sleeping porch. When it was too hot to sleep inside, the family moved to the sleeping porch.

Claudia remembers that there were always guests in the house, and that her mother entertained a lot, mostly around family. Since Grandmother Powe was one of 11 children, she had many relatives who came from out-of-town for visits, some staying as long as a month. (Claudia says one even stayed for more than a year!)

When I was a boy, Sam Ervin (whose mother, Laura Powe was Grandfather Powe's sister) made the Powe house "home" while he held court in the area. He was a popular Superior Court Judge at the time and later became famous as a United States Senator and chairman of the Watergate Hearings. I remember his sitting on the front porch recounting interesting tales from the courtroom. Being a storyteller non-pareil, he made it all sound so fascinating that I decided then and there to be a lawyer just like Cousin Sam.

Not only was our family large, but very close. You see, my mother's brother, Byers Watkins, married my father's sister Claudia -- which made my three sisters, Frances, Jo and Mary Louise and me double first cousins of Claudia's three children, Warren, Claudia and Eddie.

In 1924, the family compound in West Durham was increased when my father and my mother, Louise Watkins, decided to move into a house directly behind William Erwin's. It expanded again (after Grandfather Powe died) when Claudia and Byers built a house in the middle of my grandparents' garden, and again (after World War II) when Jesse Harper Ervin, Jr. and his wife Lu remodeled the servants' quarters in the backyard of "Sunnyside" and made it into an attractive cottage where they lived for a number of years. Time and again, for three generations, various members of the Erwin and Powe families returned to live at home or close by. Even I, and my wife and first daughter, lived in a rented house three doors beyond my grandparents' house when I came home to Durham to practice law.

One of my sister's memories of their grandmother's house is that it was often filled with boxes of scarves, sweaters, socks, pajamas, and other clothing -- all items that she had had local women come to her house to knit and sew for the Red Cross. For twenty years, she had been chairman of "production" for the Durham Chapter of the Red Cross; so for a long time, her house was the receiving station for supplies. Grandmother Powe had helped start the American Red Cross in Durham and was its first chairman. She was also a member of the Watts Hospital Board, chairman of the Durham Chapter of Colonial Dames, and long-time Sunday school teacher at St. Philip's, where her husband was a vestryman and senior warden.

Although she had a good sense of humor and a dry wit, Grandmother Powe was conservative and proper about some things. As long as she lived, she wore dresses to her ankles. My sister, Mary Louise, remembers going to Grandmother's with sisters Frances and Jo and wearing shorts. Mary Louise says Grandmother would admit them, but wrap newspapers around their legs with the opinion "You children shouldn't bare your extremities."

My grandfather died at Watts Hospital in 1929; My grandmother died in 1943. After their deaths, the house was sold to Dr. and Mrs. B.W. Roberts who, with their two sons, also have happy memories of living there. When they decided to sell, they offered the Powe house to my wife and me, but we had plans to build. Then for a number of years, the house was rented (by new owners) to Duke students, some of whom became artists, potters, musicians, and teachers. In rather a Bohemian way, they too have loved and enjoyed the old house. I imagine my grandmother would have wanted to do more than wrap newspapers around their legs.

Mill Growth

During all this time, the Erwin Mills was steadily growing. At its peak, 6,000 people were employed and six more plants were added. Sheeting and pillow casing enlarged production, and During all this time, the Erwin Mills was steadily growing. At its peak, 6,000 people were employed and six more plants were added. Sheeting and pillow casing enlarged production, and as a result, the Erwin Mills became one of the largest textile mills in the South.

In 1952, Burlington Industries bought the mills, and at that point, West Durham began to change. The new management sold the mill houses and gave the auditorium and park to the city. The Powe and Erwin houses were both sold. Hillcrest, unquestionably the most beautiful of the three, was torn down to make way for a rest home. The East-West Expressway took my parents' house, Claudia's home, the house my wife and I lived in, and the Erwin auditorium and park. In the old Erwin-Powe compound, only the Powe house and "Sunnyside" remained, both badly in need of paint and repair. In 1981, a city inspection identified approximately 39 code violations at the Powe house. The owner, Hillhaven, would not make the necessary corrections, probably because they were planning to tear down the house to expand Hillhaven Rest Home. It is interesting that the Bohemian tenants, who seemed to really care for the house, made the repairs themselves -- rather, I suppose, than be evicted. They said, however, they could not afford to paint so large a structure. But since lack of paint was not a code violation, the house was allowed to stand. Although still sturdy, its disreputable look made it appear worse than it really was. Thick trees and overgrown shrubbery and vines gave it a mysterious air.

Area Revival

Then the revival came!

In 1982, Clay Hamner and Sehed Ltd., with great vision and business acumen, bought part of the Burlington Industries' property and employed Eddie Belk, a restoration architect, to renovate the pretty, old brick Victorian Erwin Mill and make it into apartments and office complexes. Hamner had already achieved success in converting a tobacco warehouse downtown into a delightful shopping mall. "Erwin Square," as the new West Durham project is known, has been just as successful. It has attracted many Duke University associated tenants and has brought young blood and new ideas to the area. Attractive and upbeat specialty stores have replaced the tired merchandising strip along Ninth Street. A new post office and bank appeared. Now, Hamner has just announced the acquisition of the remaining 30 acres of the old Erwin Mills site and has revealed plans to build three new office buildings; the first one to be ten stories high. Also to be included are a hotel and more merchandising and residentia l space. The project, estimated at $100 million, is the largest such undertaking in Durham's history.

In the midst of this revival, Claudia Roberts Brown, an architectural historian, began gathering all the information she could find on the Erwin Mill and the Powe and Erwin houses, as well as about other significant architecture in old West Durham. She included this information in a remarkable book sponsored by the Historic Preservation Society of Durham and the City of Durham entitled THE DURHAM ARCHITECTURAL AND HISTORIC INVENTORY. Her interest in the Powe and Jesse Harper Erwin houses became so great, that she took it upon herself to launch a campaign to have them listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

E.K.Powe House Rescue

Just when it appeared that the E.K.Powe house and "Sunnyside" would be razed for Hillhaven's expansion, Brian South, a restoration developer from Charlotte, saved the day and bought both houses! Because he was unable to purchase the property under "Sunnyside," he moved it to the front yard of the Powe house and then moved the little Erwin cottage to the side yard, just beyond the porte cochere. South, who has now moved to Durham, employed Roman Kalodij as architect. Together, they have done a magnificent job of reviving these old dwellings and converting them in a most unique way into very lovely office space. Brian South and Kalodij evidently liked the place for they have retained offices on the second story of the house.

David Ross, whose company, Ross, Johnston, and Kersting was the first to purchase space in the E. K. Powe house, told me an interesting story. He said that it was his wife Ruth who influenced him to move his offices to the Powe house. He said that when she was a student living in Southgate dormitory on the East Duke campus (across the railroad tracks) she would look out her window and see the gracious old house. She fell in love with it because it reminded her of her grandmother's house. Upon hearing that the house was for sale, she told her husband, "David, we must have some of that space; it has character!" The developer, Brian South, the architect, Roman Kalodij, and an attorney, Margaret J. McCreary occupy the second floor. Duke University acquired all of the Jesse Harper Erwin house, and Dr. James Dykes has taken the small Erwin cottage.

So, that's the story--all the way from 1900 to 1987 except to say that the house was eventually listed on the National Register.

But I cannot end this piece without saying how much my entire family is indebted to all who have participated in this unusual (and we hope rewarding) restoration. The Powes and Erwins are especially grateful to the Historic Preservation Society of Durham for recognizing the worth of these dwellings and for noting the part they played in the early history of Durham. As a result, new history is already being written, and the Old E. K. Powe and Jesse Harper Erwin houses, I'm glad to say, will continue to live. Thank you.

nw:El864

reproduced

11/25/97

carh