The Stonecutters Who Built Duke University

Two of the many Italian families who came to West Durham to work as stonecutters on Duke Chapel, the Citrini's and Berini's gather in 1930. Left to right: Danny Berini, Chima Berini Citrini, Anthony Citrini, Louis Berini, John Berini, Joe Berini, Richard Berini. Carolina and Anthony Berini (front).

Duke Hospital with Duke Chapel in the background. The hospital was built at old "Bone Yard" where Durham residents brought their dead horses and cows.

July 16, 1990 marked the end of an era in the history of the construction of Duke University. On that date Louis Fara, a native of Frugarola, Italy, and the last of the original stone setters who skillfully laid the Indiana limestone trim on West Campus, died. Fara was representative of a group of laborers whose unique background and contribution will be acknowledged as long as eyes gaze upon Duke's majestic Gothic arches.

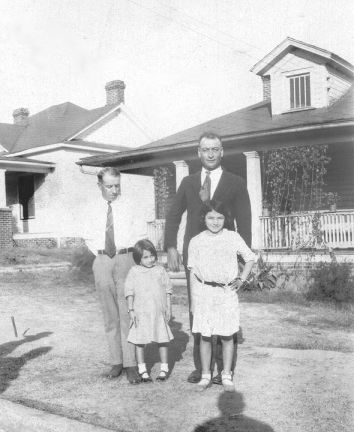

Giovanni Marzocchi with his daughters Mary and Rina (older child) in West Durham. Below: Marzocchi (left), his two daughters and a man who lived in their house (ca. 1929).

Documentation of these laborers' contributions is almost nonexistent. Photographs are extremely scarce, since construction took place during the Great Depression and laboring families did not frivolously spend hard-earned money on family snapshots. A few photographs have turned up, usually passport photos of younger men or pictures of much older men working on later commissions. Official university construction photos concentrate on architectural detail instead of the human element. The laborers' background and their sense of accomplishment have to be pieced together from scattered published interviews. Fortunately, their names are familiar, for many remained in Durham to raise their families. Six decades after the completion of West Campus the city telephone directory still lists the Italian names of Fara, Ribet, Ferettino, Citrini, and Berini. In addition, Giobbi and Greppi worked the stone as well as the highly respected stone workers Macadie and Brown. They worked along side native blacks and mountain whites who had also migrated to Durham in search of steady employment during severe economic times.

Giovanni Marzocchi relaxes on his porch after his daughter's Baptism in 1929. Rent for the family's home at 1206 6th Street was $34/month.

Each laborer became an accomplished artisan at his assigned level of work. Stonemasons worked the "rubble" bluestone from the nearby Hillsborough quarry. Often thought akin to brick layers, stonemasons did not believe the skills were interchangeable. Expert stonemasons had to have a feeling for color and design as well as the skill to size and shape each stone. These intangible and tangible qualities were vital to the West Campus project where the beauty of the stone was in its fourteen plus shades of color and where each piece was cut at a ratio of length two times height.

Zita Tonelli (right), wife of Giovanni Marzocchi, and neighbor on 6th

Street.

Same porch today (1206 Clarendon Street).

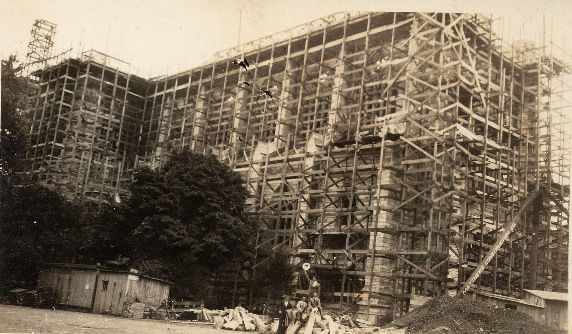

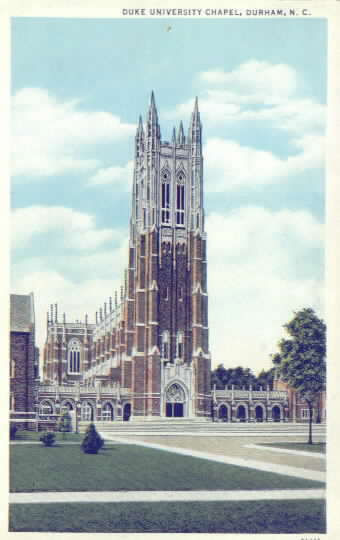

Rare photo of Duke Chapel under construction. Pietro Toma (holding hat) and Giovanni Marzocchi were considered highly skilled masons. Both men were Head Masons working on the chapel's towers. 1930 postcard of Duke Chapel is below.

Only the very best men were selected for the more delicate work with "cutstone" or Indiana limestone. They were almost all Italians working for the subcontractor James W. Brown under the supervision of Donald Macadie. Brown and Macadie were natives of Scotland who immigrated to the United States early in the century and located in the south as a result of assigned commissions. The Italians, too, were most often immigrants who came to Duke as word circulated among friends and relatives that there was stone work in Durham, North Carolina. Many had been apprenticed in the Alps of Italy, Switzerland, or France, as had been Tony Berini, for a season's pay of "food, lodging, and a suit of clothes, pair of shoes and a bright red cap." In the United States, they were working in New York City or the coal mines of West Virginia before answering the call to Duke. The stone setters set the arches and doorways throughout the campus, capping their employment with the soaring nave of the Chapel. When the campus opened in September, 1930, a select crew remained to finish the Chapel. They were doubly proud because of the special recognition of their expertise and because they were completing such a magnificent structure. It was as if every stone setter, particularly those with European backgrounds, wanted to work on a Gothic cathedral in their lifetime. As the Duke commission finished many worked on nearby government building projects financed by the New Deal, and some traveled west to build tunnels on the Blue Ridge Parkway.

The Berini family in 1924: Joe, Anthony, John, Chima, Carolina, Louis, Richard, and Danny Berini.

Richard, Joe, Dante, Louis and John Berini standing in front of the chapel they helped build. While living at 2908 Hillsborough Road in West Durham, the boys spent the summer helping older stonecutters working on Duke Chapel and the nearby hospital (ca. 1989). Courtesy of Louis Berini.

B&W photos are courtesy of Debora Antiga (Rome, Italy) and Louis Berini (Durham, NC). Text is courtesy of Duke University Archives.