Life in the Mill Village

Neighbors

share their photographs of OWD life in days gone by.

|

|

|

Proud mother (1944): Lula Everitt holds her daughter, Delores Everitt

Stansbury in yard. Almost 60 years later, Delores joined us at the Erwin

Mills cemetery cleanup.

According to James Eubanks, who grew up on Case Street, one of the attractions of Erwin Park (near present-day Duke School for Children) was a metal cage with several monkeys inside. Employees at Erwin Auditorium cared for the animals and during a feeding, two monkeys accidentally jumped out of the cage. The monkeys ran across Erwin Road and down into a pasture that Hoy and Charity Eudy used for their cows, sheep and goats (Mr. Eudy was a Weaver at Erwin Mills). The monkeys were never caught and as a result, the area around Swift and Case became known as "Monkey Bottom."

"Jim Eubanks has contributed a lot of his

time and efforts towards ensuring that our childhood memories are well

preserved in the annals of Durham's history. He has contributed countless

hours to the Old West Durham Neighborhood Association, and information

regarding the work of his and others, may be found on the Internet [see

photos throughout this site -- ed.]. "

-Major Charlie Carden (from his eulogy for the long-time resident of

Mill Hill)

Monkey Bottom (1938): Henry Browning stands in his yard overlooking

what is today the Duke School for Children (near the Durham Freeway

and Swift). Browning, his wife, Pauline, both his parents and both her

parents all worked at Erwin Mills. Most of the two families are buried

at the Erwin Mills cemetery (aka Cedar Hill) on West Pettigrew.

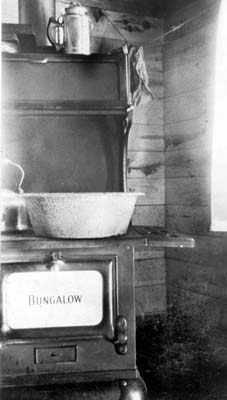

Close-up of Stove in Erwin Mill Village. ca. 1940: Bungalow Stove with

kettle, coffeepot, and pan to heat water.

Photo above courtesy of NC Collection at the Durham County Library.

Description of the Mill Village in Durham, by Osha Gray Davidson, The Best of Enemies: Race and Redemption in the New South (Scribner).

The houses were surprisingly alike on either side of this crucial dividing line [railroad tracks separating white Durham from black]: small, dark, and cramped. They had front porches in identical states of disrepair, tin roofs warped and rusted to a similar dull red hue, and flyblown outhouses in each dirt backyard. At night these houses glowed with the flickering yellow light of kerosene lanterns that lent the district an aura considered quaint -- by those who didn't have to live there...

African-Americans have always occupied the lowest level of the Southland's great social pyramid, but as the new century progressed the region seemed unable to decide who it despised more: blacks or poor whites... Mill employees labored at dangerous jobs under miserable conditions -- and for poverty wages -- breathing in cotton dust until their lungs were brown with the stuff and they suffocated... Before long, workers were simply born into mill life and very few escaped it. And although it was their underpaid labor that transformed Durham into the Jewel of the New South, their presence in "better areas" of town was not welcome. On rare occasions that they ventured out of their neighborhoods, mill hands were immediately recognized by their deathly white pallor. Passing them on the street, businessmen might smile to one another and exchange a single sharp-edged word: "linthead."

... The paternalism that governed relations between white planters and slaves in the Old South was extended in the New South to include poor white factory workers. In the early days, mill owners greeted workers by their first name each morning, inquiring about the health of children, who might also be known by their name. If a worker fell ill, the mill boss would often pay the doctor's bill. One owner hired a full-time nurse to care for workers and their families. When a smattering of education was considered a good thing for workers, some mills offered classes at night at no charge. Like a stern but caring "daddy," William Erwin, the tall bespectacled president of the Erwin Cotton Mills, pedaled his bicycle around the mill village in West Durham in the evenings, enforcing a 10 P.M. "lights-out" rule. For the workers he referred to as "my people," Erwin built a huge auditorium where they attended concerts and plays, movies and flower shows. Later he added a swimming pool, tennis courts, and even a small zoo.

Erwin's beneficence, however, did not silence the rising critics of a system that traded informal "favors" for complete submission to the owner's authority. "His mill villages are better than most other companies," admitted one union leader, "but he preaches baths, swimming pools, and that kind of thing and then won't pay a wage that is anything near even a living wage."

Aerial view shows Erwin Mills and the shops on Ninth Street. Duke's East Campus, Blacknall and St. Joseph's churches are beyond the shops. On the far right, the West Durham Post Office is reflected in mill pond -- where Wachovia Bank stands today. Some of the West Durham mill village can be seen in the foreground (Hillsborough Road was later shifted south to meet Markham Avenue). Click on photo to see enlargement.