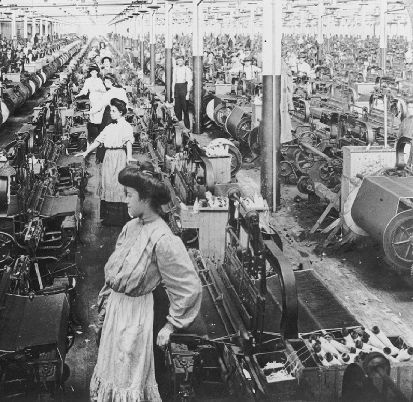

Men and women weaving at the White Oak Mill in Greensboro, NC, 1909. Courtesy of the National Museum of American History.

Like a Family: The Making of a Southern Cotton Mill World (UNC Press)

By 1900, a full 92 percent of textile workers lived in mill villages owned by the companies that employed them. Usually, the mill village included a supervisor's home, houses for workers and their families, one or more churches, a school, and the company store. In the early 1900s, most mill houses were one-story, four-room affairs, lit by kerosene lamps and heated by open fireplaces. Workers drew water from common wells and pumps, and less than 7 percent of mills in 1907-1908 had sewer facilities more elaborate than simple privies. Many manufacturers had a rule that required families to supply one worker for each room occupied, further encouraging the entry of children into the mills.

The closeness to the factory had its advantages for millhands, but it also meant that mill managers could keep close tabs on their employees, sometimes using supervisors or mill village policemen for surveillance. Mills often supported the churches in the villages, paying the salaries of ministers or providing maintenance and heat for the buildings, and, in turn, the donations from mill owners frequently shaped the message from the pulpit. Not surprisingly, some company-supported pastors preached a gospel that favored the company's interests.

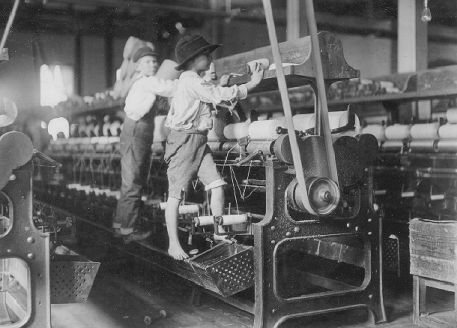

Doffers at the Bibb Mill No. 1, Macon, Georgia, 1909. Photograph by Lewis Hine. Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Service.

Mills also sponsored

village schools, sometimes providing buildings and paying teachers’

salaries. Supervisors would often send for children in the school when

extra workers were needed in the mill. "Owners had little to gain by

enforcing school attendance, since children who became ensnared by the

factory at an early age were less likely to seek employment elsewhere

as adults. These conditions improved only in the mid-1910s after schooling

was made mandatory for all children under twelve years of age. Mills

operated company stores and often sponsored a variety of other small

businesses such as barber shops and pool halls. Those establishments

were a convenience to workers, but they could also serve to keep millhands

in debt to their employers.

Mills also provided social workers, recreational activities, clubs, and educational opportunities, in part to provide better living conditions to their employees, but also to make sure that, in a time of labor shortage, millhands were satisfied enough that they would not seek employment elsewhere. Mill owners also hoped that the benefits they supplied to employees would silence critics from outside the mills who worried about poor working and living conditions, child labor, and mill village poverty. The results, however, were often disappointing. For their part, mill workers recognized that the sewing clubs, nurseries, and baseball teams offered by the companies were intended to keep them docile and loyal. Some workers refused to participate or created their own recreational activities as alternatives to company-sponsored options. Still others took part in the programs but did not buy into the company's intended message. They demanded higher pay and better conditions even as they took full advantage of the clubs and other activities.

Girls enjoying a break from work, outside a Georgia cotton mill. Photograph by Lewis Hine. Courtesy of the Photography Collections, Albin O. Kuhn Library and Gallery, University of Maryland at Baltimore County.

Company "welfare work" failed to produce dramatic results because workers drew on the strengths of their own communities to avoid dependence on their employers. Millhands brought remnants of their lives on the farm with them and insisted on having gardens, barns for their animals, and chicken coops in the villages. They socialized together, often gathering for music and dancing, and helped their neighbors during difficult times, just as many had done in rural communities. Mill workers also created their own alternative churches and held emotional revivals that worried many mill owners.

"Viewed from the outside, mill villages seemed to deny workers the most basic forms of self-expression. But in muddy streets and cramped cottages cotton mill people managed to shape a way of life beyond their employers’ grasp. Millhands' habits and beliefs were more than remnants of a rural past; they were instruments of power and protection, survival and self-respect, molded into a distinctive mill village culture. Sometimes that culture simply defended workers against condescension and economic hardship. At other times, it bred a spirit of independence that threatened the village's purpose as an institution of labor control. In either case, it offered assurance that mill folks were ‘fine, honest, hard-working people.’"

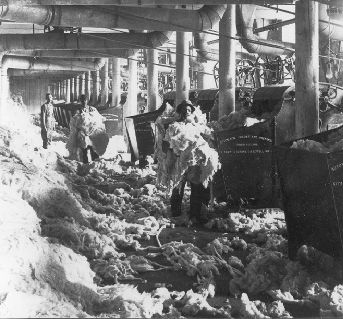

Men opening bales of cotton at the White Oak Mill in Greensboro, North Carolina, 1907. This was one of the few cotton mill jobs available to African Americans. Courtesy of the National Museum of American History.

Mills and More Mills

by Myrick Howard, Executive Director, Preservation North Carolina (who attended EK Powe School on Ninth Street)

Preservation North Carolina has been increasingly involved with the preservation of the state's industrial heritage - working to preserve mills and mill villages across the state. Why the great interest in the state's industrial heritage? The properties with which our revolving fund works tend to reflect both the state of preservation and the economic trends in North Carolina...

Today, the the distressed properties of choice for preservationists are industrial properties. Our work with mill properties is merely a reflection of changes in North Carolina's economy. North Carolina's industrial base has been changing this decade in response to changes in the global economy. The state's traditional industries -- textiles, tobacco manufacturing and furniture -- are faced with international competition. As a result, businesses which do not move to third world countries are focusing on manufacturing efficiency. The giant factories built at the turn of the century are being vacated at a dizzying pace. According to a 1997 article in the Raleigh News and Observer, 138 textile mills had been vacated in North Carolina in the previous seven years. That pace has not slowed.

These historic industrial properties present both challenges and opportunities for local communities. A large vacant mill can be a cancer, if it remains vacant and unused. Neighborhoods and commercial districts surrounding a vacant mill will deteriorate and crime will increase. The building itself will be subject to vandalism, vagrancy and arson. Businesses and individuals looking for relocation opportunities will perceive a huge abandoned building as sign of community deterioration. The community spirals downward.

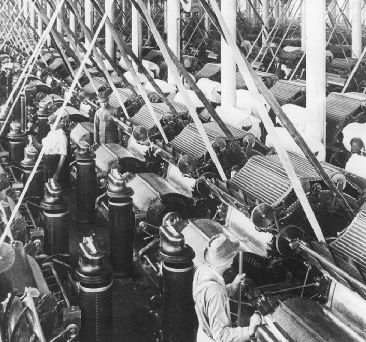

The card room at White Oak Mill in Greensboro, NC, 1909. Fast-moving belts and powerful machines made carding a particularly dangerous job. Courtesy of the National Museum of American History.

Renovated for new adaptive uses or for new industrial or business uses, a large old factory or mill can provide an economic boost. Used as apartments, condos, offices or shops, it may attract tourists and stimulate new economic growth.

In larger cities, the reuse of large old industrial buildings is relatively easy. The spaces are inexpensive to purchase and renovate; the buildings are often located close to downtowns and can play a role in downtown revitalization. Rents or sales prices can justify upfitting for new uses. North Carolina's new rehabilitation tax credits aid immeasurably in making such adaptive uses financially feasible.

One thing we have learned over the years is that the environmental problems at old mills are not necessarily as bad as the rumor mill asserts. We heard over and over that Loray Mill [Gastonia, NC] was highly contaminated, but the environmental assessment didn't bear that out at all. A 1993 real estate appraisal wrote Glencoe [Burlington, NC] off as undevelopable because of supposed environmental hazards, but scientific analysis revealed few problems. The lesson is to ascertain the facts about environmental conditions rather than listening to hearsay.

We have also learned that the interest in preserving these industrial buildings is widespread and contagious. The mill houses have been popular for a "new breed of buyers" (to quote an article from The Wall Street Journal about mill villages), and the idea of trendy condos in towns denigrated as "blue collar" has been catching on. City and county officials, chambers of commerce, and others have joined with preservationists in working to find new uses for industrial buildings.

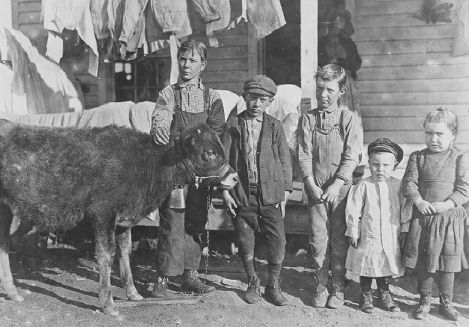

Caring for livestock, one of children's most important responsibilities. These children lived at the Wylie mill village in Chester, South Carolina, 1908. Photograph by Lewis Hine. Courtesy of the Photography Collections, Albin O. Kuhn Library and Gallery, University of Maryland at Baltimore County.

Books on Southern Cotton Mills

Andrews, Mildred Gwin. The Men and the Mills: A History of the Southern Textile Industry. Macon, GA: Mercer, 1987.

Barnwell, Mildred Gwin. Faces We See. Gastonia: The Southern Combed Yarn Spinners' Association, 1939 picture essay of mill life in Gaston County, NC).

Beatty, Bess. "Textile Labor in the North Carolina Piedmont: Mill Owner Images and Mill Worker Response, 1830-1900." Extract from Labor History, vol. 25, no. 4 (Fall 1984).

Cash, Wilbur J. The Mind of the South. New York: A.A. Knopf, 1941.

Clark's Directory of Southern Textile Mills. 1912-1970. Charlotte: Clark Publishing Co. (semi-annual).

Conway, Mimi. Rise Gonna Rise: A Portrait of Southern Textile Workers. New York: Anchor Books, 1979 (portrait of Roanoke Rapids, NC, that addresses important issues such as protest in the industry and brown lung disease).

Glass, Brent D. The Textile Industry in North Carolina: A History. Raleigh: Division of Archives and History, NC Dept. of Cultural Resources, 1992 (history that addresses the social changes that accompanied the rise of the textile industry).

Hall, Jacquelyn Dowd et. al. Cotton Mill People: Work, Community, and Protest in the Textile South, 1880-1940. Washington, D.C.: American Historical Association, 1986.

Hall, Jacquelyn Dowd, et.al. Like a Family: The Making of a Southern Cotton Mill World. Chapel Hill: UNC Press, 1987 (study of the mill village community based on oral history interviews in the Carolinas).

Herring, Harriet Laura. Passing of the Mill Village: Revolution in a Southern Institution. Chapel Hill: UNC Press, 1949 (studies the social effects on the community when mill homes are sold).

Hodges, James A. New Deal Labor Policy and the Southern Cotton Textile Industry, 1933-1941. Knoxville: Univ. of Tennessee Press, 1986

Leiter, Jeffrey, Michael D. Schulman, and Rhonda Zingraff, eds. Hanging By a Thread: Social Change in Southern Textiles. Ithaca, NY: ILR Press, 1991.

McHugh, Cathy L. Mill Family: the Labor System in the Southern Cotton Textile Industry, 1880-1915. NY: Oxford University Press, 1988.

Mitchell, Broadus. The Rise of Cotton Mills in the South. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press, 1921.

Pope, Liston. Millhands and Preachers: A Study of Gastonia. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1942.

Rhyne, Jennings Jefferson. Some Southern Cotton Mill Workers and Their Villages. Chapel Hill: UNC Press, 1930 (largely quantitative social study of workers in Gaston Co, NC).

Standard, Diffee W. and Richard W. Griffin "The Cotton Textile Industry in Ante-Bellum North Carolina," in North Carolina Historical Review vol. 34, nos. 1-2. (January-April 1957).

Tompkins, Daniel A. Cotton Mill, Commercial Features: A Text-Book for the use of Textile Schools and Investors. Charlotte, NC: D. A. Tompkins, 1899 (useful sociological study that shows cost of machinery, equipment, and mill houses, including floor plans).

Young, James Richard, ed. Textile Leaders of the South. Anderson, S.C., 1963.

courtesy of UNC's NC Collection