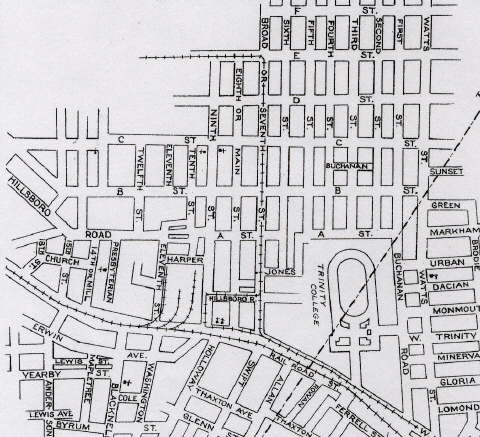

Wells & Brinkley Co. 1920 Map of West Durham

Map image courtesy of Lynn Richardson, Durham County Library

Trinity College is shown on the right while the Erwin Cotton Mill is on the left (where the three railroad spurs extend north into the mills). The West Durham mill village (ca. 1892) is north, west and south of the mills and Trinity Park is east of the college. Developed in the early 1900s, Walltown and Trinity Heights are north of Trinity College.

Originally, Trinity College administrators wanted to expand the campus to the north. When word of these plans got out, landowners in Trinity Heights jacked up their real estate prices and college officials started looking at the Rigsbee farm south of the Erwin Mill village. Because of loose lips, Duke Chapel is not standing near the corner of West Knox and Onslow. And the Duke football team plays where the Rigsbee's used to keep their pigs -- on what is now West Campus.

When Walltown was first developed, it's east-west streets were lettered and its north-south streets were numbered. So, Ninth Street is called Ninth Street because of Walltown.

Because other parts of Durham already shared some of these street names, many streets were changed after West Durham was annexed into the city in 1925. Holloway, Blacknall, Washington, Church, Buchanan and Sunset all had sister streets elsewhere in the Bull City. What was Eleventh & B Street became Virgie & Green and what was Main & Hillsboro Ave is now Iredell & Perry.

The dotted line on the map represents the old city limits (and explains why Buchanan is called First Street, north of A St/Markham). Avoiding city taxes, Erwin Mills objected to annexation for many years (not having city water explains why the mill village had out houses until 1925).

Note the trolley tracks following West Main past Trinity College to West Durham. The original trolley ended at the mills on Ninth Street. Later, the trolley tracks formed a small loop around the southern end of the Ninth Street shopping district. When Watts Hospital and Club Blvd Estates were built around 1910, the trolley was extended north along Broad (7th St) and out Club Blvd (E Street) -- creating one of Durham's first "streetcar suburbs."

The communities around East Campus are crisscrossed with deep gullies and creeks. When this area of Durham was first developed, wealthy interests purchased the highlands for larger homes -- leaving bottomlands for smaller dwellings in gullies. If you drive along the length of Englewood Avenue (D Street), for instance, you'll see larger homes in elevated areas, smaller homes down in the stream valley and bigger houses back at the top of the next hill.

Life in a Mill Village

Between 1892 and 1920, thousands of white farmers were drawn to the jobs at places like Erwin Mills in West Durham. No longer did they follow the shifting rhythm of the seasons. They marched to the regular summons of the factory bell.

With the mills came the mill towns. Manufacturers created these villages to give their workers a sense of community and to encourage them to rely on the company. But the rise of the textile industry meant little to the newly-freed blacks. The mills gave them only unskilled jobs, work no one else wanted.

Mill Worker's House

A mill worker's house was plain, but it was better than a sharecropper's shack. Rooms often had more than one purpose. A typical bedroom in a 1925 mill house would have also been a sitting room and a work room. Workers brought some furniture from the farm. The rest they made at home or purchased at the company store.

Houses were usually owned by the company. Monthly rent averaged 50 cents a room. Most houses had four to six rooms, including a kitchen and were heated by coal. By 1925, most mill houses had electricity and plumbing (making the outhouses in the back yard obsolete).

Village life centered around the mill. A typical shift in the early 1900's began about 6 a.m. and lasted about 12 hours. Mills operated Monday through Friday and a half day on Saturday.

Wages were low, an average of $20 a week in 1920. Women and children had to work to help support their families. Women usually worked in the weave rooms and the spinning rooms. They were generally paid less than men.

Until the early 1900's, children as young as 6 labored in the mills. Some swept floors. Others changed bobbins. Even though youngsters worked the same hours as adults, they were paid less. By 1916, federal laws had reduced the number of children in the mills. However, at age 14, many began a lifelong career as factory workers.

Blacks were prohibited from working with whites. They were hired, at low wages, to clean restrooms, maintain the grounds, work on loading docks, and deliver groceries in the village. They were paid so little that even some mill workers could afford to hire black housekeepers.

Mill villages were self-sufficient communities were often built outside incorporated towns. Designed by Northern architects, the buildings, including the mill, often looked as if they could have come from New England. Many houses were two-story frame "saltboxes" with peaked roofs. L-shaped and T-shaped houses were also common (ie. along West Knox Street).

In the 1920's, a typical mill village would have about 1,800 mill employees and their families living in some 350 houses within walking distance of the mill.

Mill villages were often on the railroad line which brought in raw materials, took the mill's products to market, and carried passengers.

Mill companies often sponsored baseball teams. During the warmer months, workers hurried to the ballpark after work for an early evening game. Like Erwin Field at Main & Broad, the diamond might also be used for women's softball.

Because many youngsters worked in the mill, the first school was small. After passage of a child labor law in 1916, more children went to school, at least part-time. Most children attended through seventh grade. Few went to high school. Night classes in reading and writing were available to adults (often in the company library).

A person's job in the mill, not the number of people in his family, determined the size of his company-based house. Many families lived in three rooms: some in six-room duplexes and some in single-family houses. The supervisors' homes had up to nine rooms. Rent was deducted from workers' pay.

In the 1920's residents found it easier not to have grass in their yards, but they kept the dirt neatly swept. Many grew vegetables and kept livestock in their backyards. Cows grazed in pastures set aside in each section of the village (Erwin Mills kept sheep grazing on the mill grounds). Unmarried workers often lived in the mill-owned boarding house.

The plant manager's house was often near the village and may have the only home telephone in town. The manager may have allowed residents to use his phone and his yard might have been the site of community parties.

Village stores sold everything workers needed, including food, fuel, cloth, shoes and even coffins. Groceries were delivered by wagon. If a worker did not have cash, he could go to the mill office and get tokens called "loonies" or "dugaloos." He could spend them at the store and have the amount deducted from his pay.

"I guess there were 200 houses on this village... It had its bad points; we didn't make much money... But like I said, it was kind of one big family, and we all hung together and survived." -Hoyle McCorkle, a retired mill worker

Community spirit was strong in mill villages. Adults worked for the same employer. Children attended the same school.

Sports were the most popular community activities, and competition was fierce. Companies were not above recruiting worker-players from other mills. A good team could give a village state-wide recognition. (We've learned that Durham mill teams recruited Italian stonecutters like Giovanni Marzocchi.)

The Fourth of July was a major holiday. Companies often sponsored celebrations. On lesser days, a picnic, a concert, a box supper or a parade could bring the village together.

The workers were also united in times of sorrow. When illness or disaster struck, they helped each other, as they had in the farm communities of their past.